Three days before the graduation of the class of 1994, senior Ron Hanks got a personal phone call from Principal Rudolph Howard. Howard informed Hanks that if he came within 1000 feet of the school or distributed his newspapers, he would face immediate expulsion.

In his final semester of highschool Hanks had an experience that not only shaped him as a person, but journalism itself for students in Arkansas.

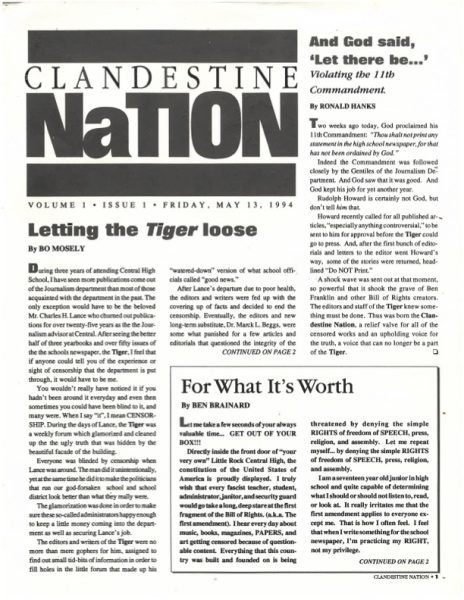

As co-editor in chief of The Tiger, Hanks encountered a major shift in the newsroom when his previous journalism teacher Charles Lance retired and the new advisor gave the student reporters full autonomy over the newspaper.

“[The Tiger staff] were really excited because now we were writing everything we wanted to write,” Hanks said. “We just had our own angle, so even if we were telling a story about, you know, semi finalists or something it was from our own voice.”

With new issues released weekly, Hanks and his staff wrote what they noticed happening around them without holding back, which encouraged fellow students to come to them and share their personal experiences at school.

“And because we were sort of empowered already, we were emboldened to write what we wanted to write,” he said. “We just wrote them. No problem. Like, didn’t think twice.”

While this brought more power to the students, unfortunately Principal Howard did not agree. He demanded to read over and approve each issue before it was printed. He redlined multiple stories, even going as far as drawing X’s and writing “do not print” over entire pages.

“[The articles] were not even bad stuff. Like, some of it was violence happening outside the school or on the school property, but it really wasn’t that bad, you know?” Hanks said. “So anyway, that’s basically how it started”

Hanks realized that Howard’s demands prevented them from spreading awareness about important issues happening on campus, so he took action. He contacted Mara and Alan Leveritt at the Arkansas Times, and they allowed Hanks to use their computers to print the stories that Howard was censoring.

“[The Arkansas Times] helped basically oversee the stories that we wanted to write,” he said. “And they were with us full on.”

On the night of May 12, three days before graduation, Hanks received a call from Howard, who asked to speak to his mother.

“Everything was dramatic, and then he’s just going off on her,” Hanks said. “So then I’m like, ‘what happened?’ And she’s like, ‘if you go to that school tomorrow and you distribute those newspapers, you’re gonna be expelled.’”

Some of his peers on the newspaper staff dropped out right then, but Hanks took a stand. He called Channel 7 and 11, Fox News, and the Democratic Gazette.

“I just called everyone and I was like, ‘s**** going down. You need to come to Central High School because the students are rebelling,’” he said. “We just were not gonna take it, you know, at all.”

On Friday May 13, Channel 4 reached school before Hanks and informed Howard that he literally could not bar a student from coming to school. They had disarmed the situation so when Hanks arrived, he distributed his newspaper on the sidewalk. He was able to finish the school year, but not without challenges.

“Yeah, things got really real those last three days too, you know, I had teachers cuss me out, and I’m like, 17 years old,” Hanks said. “But it changed me, right? It’s one of the things that that cemented in me, a part of knowing right from wrong”

Hanks’ experience was on the front page of the Democratic Gazette, after getting interviewed many times his story was told all weekend.

“It just sort of propelled me to want to do more. At the time, there were only five states that had any kind of [journalistic] protection at all in the whole United States for high school students,” Hanks said. “And that led to the next year, working on the legislation”

The summer after his freshman year of college, Hanks interned with the Arkansas Times and testified at the State Capitol. They proposed the Arkansas Student Publication Act, which made it through The House and Senate, and was passed in 1995.

This experience encouraged Hanks to continue a path in journalism. In college he realized he was more interested in visual journalism, which spurred a short career in theater in New York and his current passion of acting and producing in LA.

“I think that happening when I was 17, it did humble me but it has guided me as I’ve gone on through my life of trusting my gut and knowing that we have, we have to speak up for each other,” Hanks said. “Now I’m putting those stories on television, and that hasn’t changed for me. That life mission hasn’t changed for me one bit.”

Hanks has traveled the world, going to places like Ecuador, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Tanzania to put people’s stories on screen. He worked with Billboard Music and Olivia Rodrigo, produced a show with Guy Fieri, as well as some of his personal projects.

“In our life, everywhere I feel like people put ladders in front of us all the time, and some of those ladders really can lead you somewhere, but many of those ladders can lead you to nowhere,” he said. “The only way to overcome ladders to nowhere is be prepared and make sure you look up wherever your ladder is going”

From getting censored his senior year of highschool to his most recent project in the Galapagos Islands, Hanks continues to climb his ladder and make a difference by telling the stories that matter.

“I feel like I got really lucky because all my ladders were leading to somewhere, and I get to keep building on those.”