When she was six-years-old, Astha Patel moved to the United States. She spent her time reading bills and talking to adults instead of playing outside. Patel and her brother, Dev, became translators after moving from Nairobi, Kenya because their parents could not speak English.

“Me and my brother had a lot of pressure on ourselves to help my parents with stuff that we shouldn’t have to help them with,” Patel said. “It was hard on us at a young age because we had to grow up a lot more.”

Now a sophomore, Patel feels she missed out on childhood experiences because she had to mature quickly.

“I feel like people talk to me about stuff that they did in their childhood, and I’m thinking, oh, wait, I never did that,” Patel said. “I kind of feel left out that I never had the same opportunities, but I can’t really do anything about it now.”

Patel’s childhood experiences are a reality for many first-generation immigrant kids throughout the United States. These kids often juggle school, work, friendship, culture shocks, and language barriers, while still working to keep their home country’s culture alive.

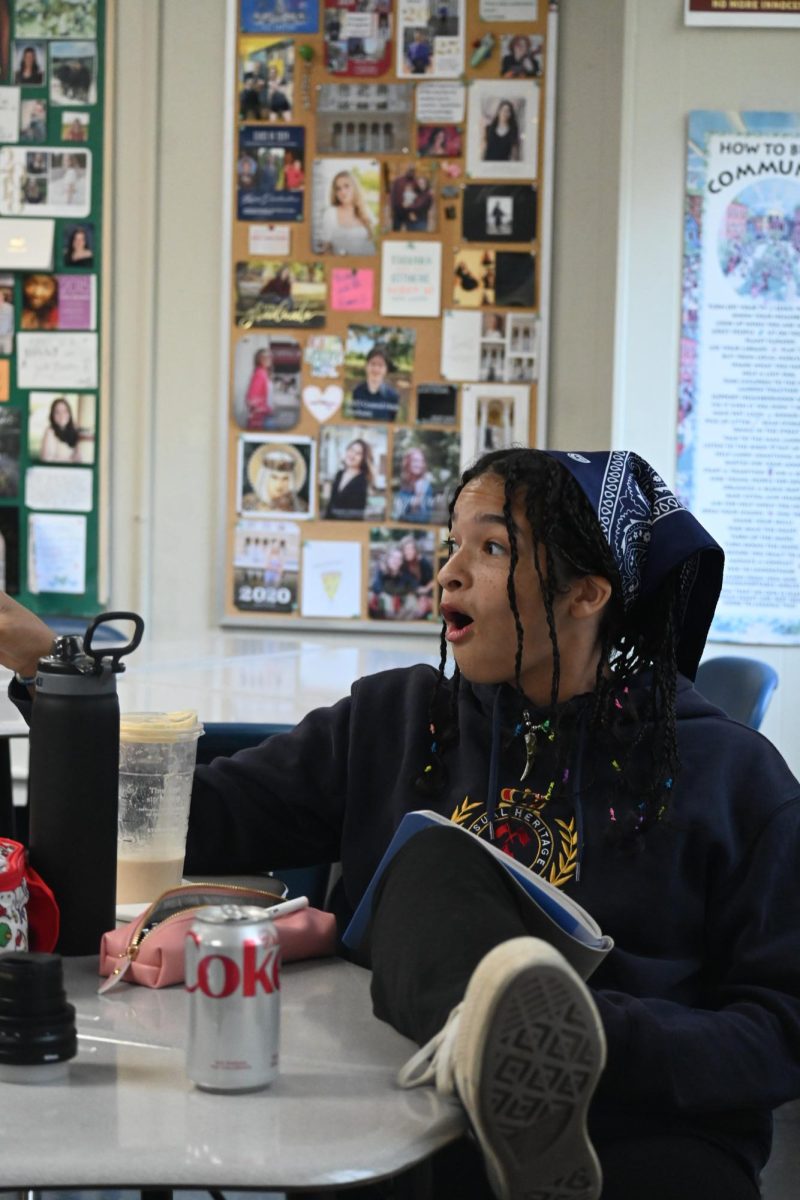

Sophomore Rawan Al-Sudani moved to the United States from Iraq three years ago and describes the culture shocks she experienced.

“If a dude really wants to date you in Iraq, they would go to your father first, not you,” Al-Sudani said. “And that was [for me], mostly, the biggest culture shock.”

Immigrant students, like Al-Sudani, often cope with these changes by keeping their home traditions alive. Al-Sudani’s favorite tradition to celebrate in Iraq was Eid, which marks the end of Ramadan, and after her move to the United States, Al-Sudani preserved the tradition in her home.

“As kids, we would get money and stuff [during Eid], which was really cool,” Al-Suandi said. “Then we would visit my grandpa, cousins, and uncles.”

Likewise, Patel’s favorite tradition is celebrating the Hindu holiday, Diwali. However, living in the South has shaped the way Patel celebrates important religious holidays.

“Back in Africa, or India too, there are a lot of people that gather together,” Patel said. “Here, we’re more limited to celebrating it at home with just my family members and we don’t have other people to celebrate it with.”

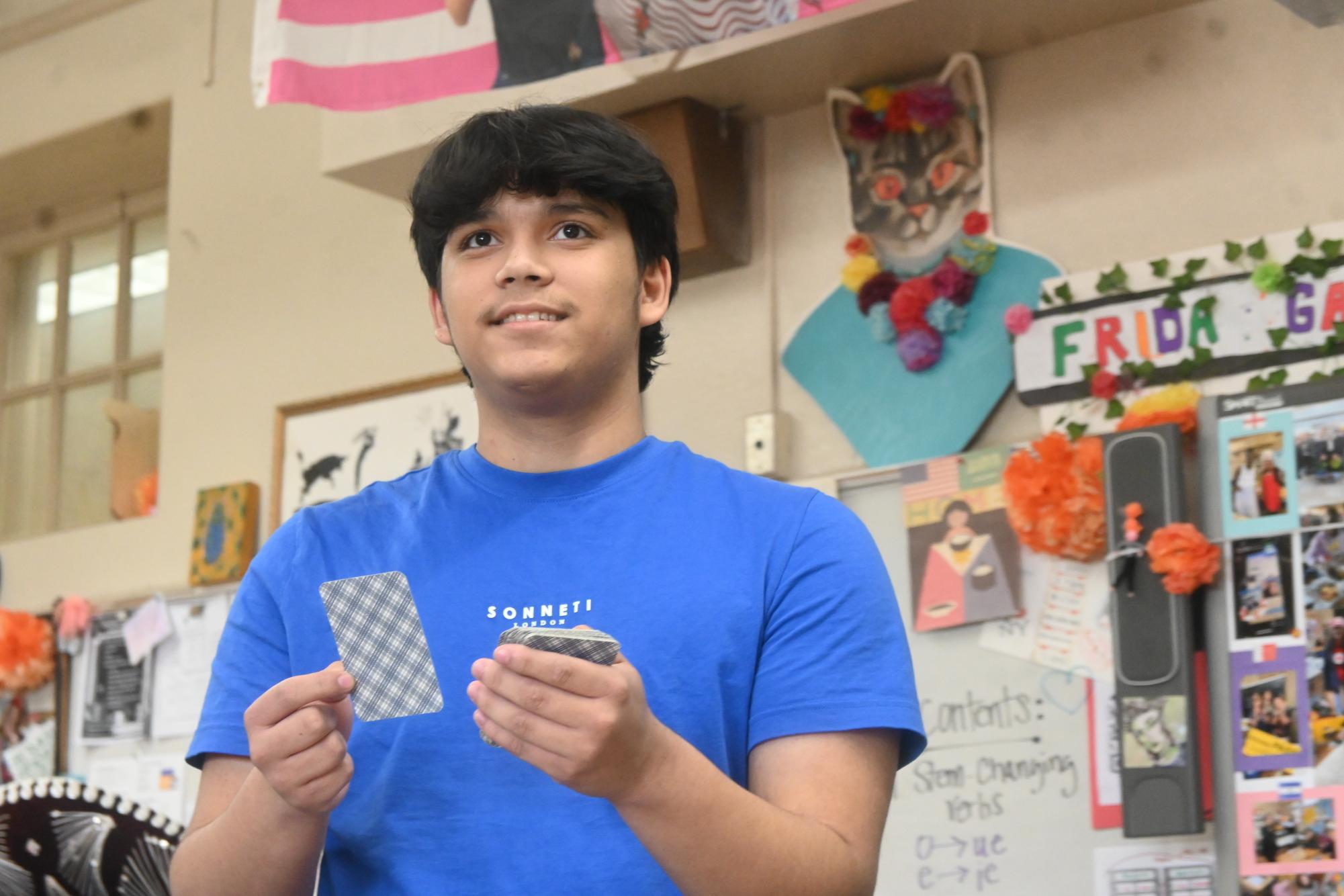

Junior Fabeio Daz, another first-generation immigrant student, found a community through religion after moving to the United States from Nicaragua.

“My favorite tradition is a celebratory form of church where we go to different churches to drink coffee and sing,” Daz said.

Since his move, Daz hasn’t found a solid Nicaraguan community outside of church. Luckily another student, sophomore Saúl Franco has been able to find friends from similar backgrounds. Franco’s community mainly includes Spanish speakers because he does not speak English, leading him to face challenges after moving to the U.S.

“In Colombia, I could go anywhere I wanted,” Franco said. “I didn’t have as many problems.”

While Franco feels trapped by his own language barrier, Patel felt responsible for her parent’s difficulty with a new language.

“I guess I feel like a lot of people that immigrated from different countries have a similar story,” Patel said. “Their parents didn’t know English, or they didn’t understand half the stuff going on here.”

However, working through a language barrier in an unfamiliar country is just one piece of the puzzle for students like Patel.

Like many young immigrants, Patel had to leave a large part of her life in Kenya.

“I miss all of the people there and just the atmosphere in Kenya,” Patel said. “You don’t feel uncomfortable or out of place because you feel like you’re in your home.”

Melanye Villanueva-Sotelo translated for Saúl Franco and Fabeio Daz during the interview for this story.