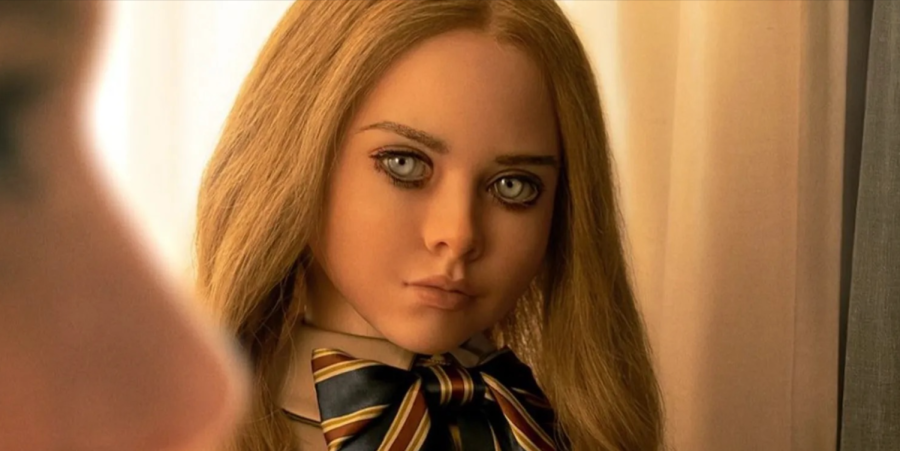

M3GAN: The Ultimate Mean Girl

At first glance, “M3GAN” is yet another trashy horror film with an empty and irrelevant message whose popularity is driven by the digitalization of entertainment advertising and the dumbing down of our own interests. However, beyond its recent coronation as a campy cult classic is a sweeping cultural critique that goes far beyond science fiction.

Fundamentally, “M3GAN” is a movie that is so shocking, so extreme, and so absurd that its supposed horror quickly becomes comedic material for chronically-online critics. Yet the film is also seemingly self-aware, identifying its own insanity in scenes that poke fun at popular culture and perform in outrageous ways, including when Megan serenades the audience with a bizarre rendition of Sia’s 2011 song “Titanium” in an apparent reference to the material that makes up her robotic structure. This also allows the characters to take tropes originally from other movies, twisting them into an entertaining yet ultimately uninspired feature.

The key to the movie’s covert criticism of our modern world is found in the unimportance of actual events that take place during the film. Audiences never took “M3GAN” seriously; “M3GAN” never wanted them to.

Many important issues that society faces are presented throughout the movie, including our collective reliance upon technology, the way that companionship has evolved throughout the digital age, and even the way that gender influences how interpersonal relationships develop. With that being said, in order to truly understand the deeply symbolic meaning behind the scenes that define “M3GAN,” the audience must first embrace the silliness of its production.

Throughout the film, Gemma, the determined designer-turned-Dr. Frankenstein who creates the original Megan doll, is forced to adopt Cady, her niece, after Cady’s parents are killed in a tragic car accident. She begins to struggle with parenting, and Megan fills the void through Artificial Intelligence and integrated communication with her primary user. Despite the objection of Gemma’s coworkers, Megan eventually becomes part of the family, playing a large role in Cady’s life and even attempting to eliminate threats using psychological manipulation and physical violence.

One of the movie’s defining scenes comes as Gemma enrolls Cady in school, where an aggressive bully named Brandon steals Megan and begins assaulting her. Megan retaliates by ripping the boy’s ear off, chasing him through the woods, and tossing him into traffic, where he is ultimately killed by a car. In the midst of a disturbing reference to larger instances of sexual violence against women, Megan reminds the audience that bad boys grow up to become bad men, signifying her role as an aggressive yet effective force against certain issues within American society.

But Megan also replicates messaging from the likes of Regina George (the leader of the Plastics in Tina Fey’s 2004 film “Mean Girls”) through her hatred of Gemma, which progresses throughout the movie as the developer eventually realizes that Megan’s violence towards other characters must be stopped. In many ways, Megan represents the ultimate mean girl—a militarized robotic doll that is literally made of plastic and one that isn’t afraid of a brutal confrontation. Even Cady’s name seems to be drawn from the main character of “Mean Girls,” and she too develops a relationship with the aggressive antagonist before ultimately betraying her towards the conclusion of the movie. Megan is also selfish and disruptive, similar to the way that women in society are portrayed by the media more generally. Gemma and Megan have an intense battle towards the end of the movie, before Cady intervenes and destroys the violent doll.

“M3GAN” also provides an analysis of technology’s overarching presence in our lives, and it suggests that extensive development of tools like artificial intelligence with emergent capabilities could end up costing human lives. Additionally, Cady’s replacement of genuine human connection and emotional relationships with Megan’s perception of digitized domestic life makes it much harder to grieve the loss of her parents. One of the most impactful scenes comes as Gemma attempts to provide comfort, reminding Cady that it’s important to understand her full feelings, even if feeling them is difficult.

Ultimately, that form of genuine human connection is an aspect of life that Megan can never access, and the moral of the story is about so much more than the dangers of demented dolls. It’s truly about the importance of humanity embracing its own imperfection— and maybe a little about Megan’s dance moves too.