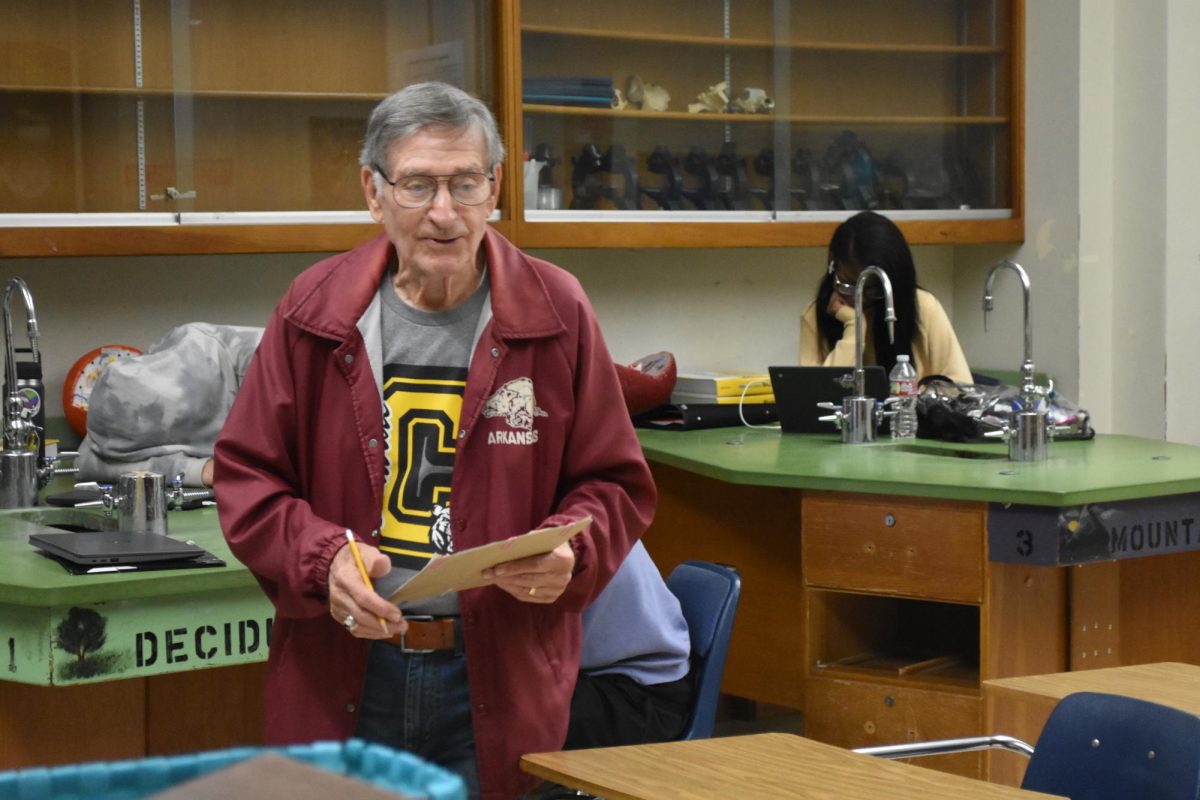

Substitute teacher Peter Hartstein has a brand. It starts at his signature blue jeans and red Arkansas Razorback windbreaker although it’s his relaxed attitude and infectious smile, which follows him into every classroom, that establishes him as a student favorite. But what students wouldn’t guess about the 86-year-old is that he spent the first ten years of his life in war-torn Europe, living under the terror of the Nazi regime.

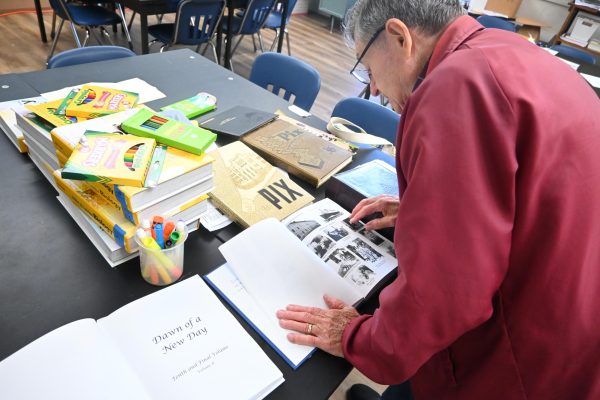

Hartstein’s family history is chronicled in a ten volume book series compiled by his cousins, who operated a paper company in Atlanta after immigrating to the United States in 1938.

“These are all letters that have been translated from German to English, and it talks about the war. A lot of these letters are between my aunt and my father because she would send rations to us and stuff that we didn’t have,” Hartstein said.

Alongside the letters inside the books’ plain, stoic covers are photos of family stores that were ransacked during Kristallnacht and portraits of family members taken by the Nazis. On other pages, there are family trees, lists of names, and unsettling streaks of yellow highlighter denoting those slain at the hands of the Nazis.

Hartstein’s father, a Jew, was taken to a concentration camp twice. The first time, at Dachau in 1938, he was released on the assumption that he and his family would emigrate to Argentina, but by that time, Argentina had closed its doors to Holocaust refugees. The second time, the Gestapo took Hartstein’s father Kurt to Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia. Invading Russian forces liberated the camp in the summer of 1945, over a year after he entered the camp.

“The reason they didn’t kill him to begin with was because he was useful to the Nazis. He was some sort of an electrician, so he could be of value to them,” Hartstein said. “Now, Kurt’s sister and some of the other relatives were sent to Auschwitz, and they killed them in the gas chambers.”

Hartstein says his father never spoke much about his time in contraction camps, and he says it is only recently that he has spoken about his own experience during the war.

“I gave a talk at church, and then the publisher of the Democrat Gazette, Walter Hussman, wanted to do a story. I went to a couple of schools, but I’m not real good about speaking in front of people,” Hartstein said. “But then, you know, I got to thinking that if I tell about what’s happened, maybe it’ll prevent it from happening again. Evidently it doesn’t help. Look at Palestine and Israel right now. It’s terrible.”

Because they were born from a mixed-marriage, one between a Jew and a non-Jew, Hartstein and his siblings largely avoided anti-Semitic violence. Most of their experience he described involved moving around Germany to avoid Allied bombing while his mother Mary tried to free Kurt through negotiation.

“My mother’s grandparents lived in a little town named Guben, and it was close to Berlin. Before we got to Guben, one evening while we were still in Stuttgart, our street was completely bombed. I don’t remember a lot of stuff, but there are some things that I remember vividly,” Hartstein said. His voice softens. “We went out of our basement, and there was fire everywhere. All the houses’ rafters and everything was burning. We had no idea which way to go to get out of there. Somebody came along in a wagon. He put myself and my sister on the wagon and threw a wet towel over us. He took us maybe a block and a half from where we were. He knew how to get to a place where there was no fire, and my sister said to my mother must have been an angel sent from God. We don’t know who that was.”

In 1947, Hartstein and his family immigrated to the United States aboard the SS Ernie Pyle with many other refugees. Shortly before the family left Europe, Hartstein’s brother Harry was born.

“The reason he was named Harry was because at that time Harry Truman was the president of the United States, and my father sent a letter to the president telling him that he was so appreciative of being in the United States that he named his son after him,” Hartstein said.

Hartstein and his family ultimately settled in Little Rock, reuniting with other family members who immigrated before the war.

“We had a modest home. My father was very satisfied. He just wanted to make sure that our family was taken care of. That’s the reason we came from Germany. He was a Jew. My mother was a Christian, and that’s the reason we were able to immigrate right after the War,” He said.

Hartstein attended the now closed Woodruff Elementary School where he learned English and met Brooks Robinson. Robinson graduated from the school in 1955, a year before Hartstein, and played 23 years as third-baseman for the Baltimore Orioles. Hartstein recounted some of his favorite stories about Robinson in the Class of 1956 newsletter after the baseball player’s passing Sept. 26.

“Brooks Robinson and I communicated about once a year,” Hartstein said. “When I went to Woodruff, I remember playing touch football with Brooks. Winkler’s was across the street from Lamar Porter Field, and that’s where I got my first taste of French fries. When Brooks went to Central, Wilson Matthews wanted him to play football, but he played basketball for Coach Haney. As everyone knows, Brooks was an all around athlete. I watched the Doughboys (Robinson’s baseball team) at Lamar many times. He was not only a great athlete, but a great human being. He came to Little Rock several times, and he donated help to renovate Lamar Porter Field.”

Hartstein’s class was recently honored at a Gala held by the school’s alumni organization The Tiger Foundation Oct. 16. The Class of 1956 has built a reputation for being one of the school’s tightest knit communities. Over 65 years after their graduation, their jazz band regularly convenes for performances, and the newsletter in which included Hartstein stories about Robinson is sent out weekly by class member Mary Lou Medlock.

“There are a whole bunch of different stories from different people in our class and she publishes all of it every Thursday. She goes into a lot of historical details that we enjoyed when we were going to school, but to have somebody like that is amazing,” Hartstein said.

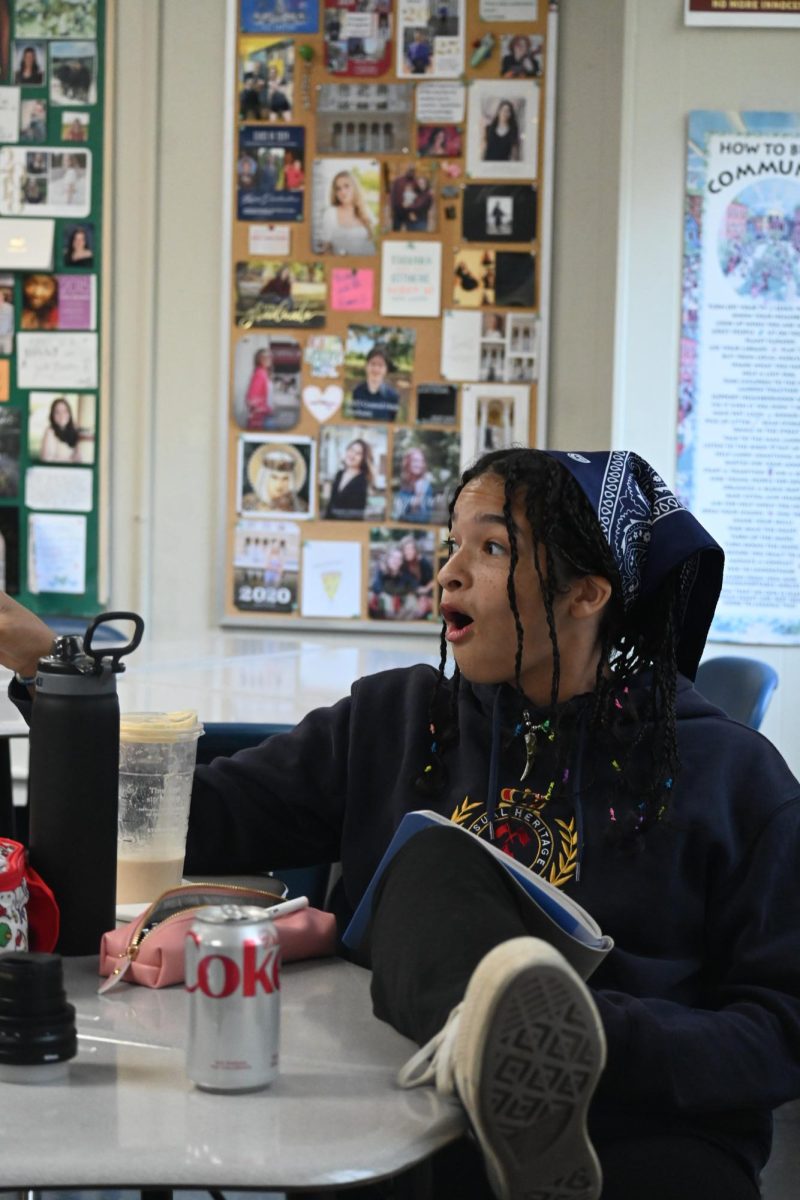

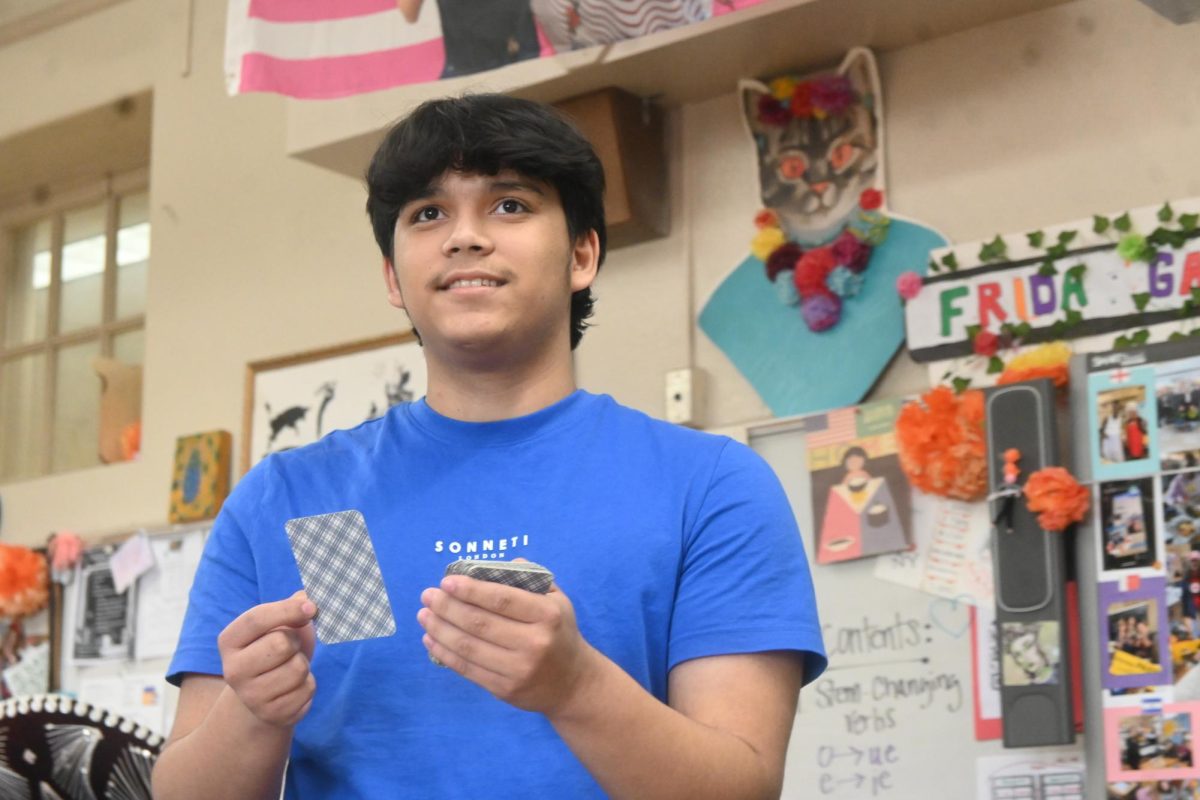

Besides the familiar classrooms and hallways, Hartstein doesn’t see many similarities between the school he attended and the nature of the school today. He points to discrepancies between AP and regular classes as well as distractions caused by modern technology as the major differences between his classmates and the students in the classes he substitutes for.

“I try to be positive when I come into a class, and hopefully the students will try to be successful. I give the assignment, you know, after that, there’s not much I can do as far as whether they do the work. I encourage them and let them know that it’s best so that they can succeed,” Hartstein said. “But some students don’t understand. In some cases, they don’t do anything. Unfortunately, cell phones are an obstacle that teachers have to contend with, which is not a good thing.”

He believes success in school was expected when he attended the school, but because of an increase in adverse circumstances facing students, that has changed.

“Most of our students came from what I call a normal family home. Students are expected to do well. You’ve got a lot of students in that classification here, but there are some who, unfortunately, don’t have that,” Hartstein said. “My background has something to do with the way I operate. My parents didn’t have to tell me. I know what their expectations were. I made A’s and B’s, and I was in Beta Club, National Honor Society, and Key Club.”

Hartstein has also observed how the community surrounding the school has both changed and remained the same over time.

“A lot of the houses are still the same homes, but say the house that I used to spend the night with a friend of mine, it’s an empty lot. It’s been that way for a good while now,” Hartstein said.

Despite all the changes both in the community and in the school itself, he views the teachers as just as dedicated as they were 66 years ago.

Memories and an enduring sense of school spirit are some of the reasons that Hartstein chooses to serve as a substitute teacher nearly every day of the school year, but another reason he keeps coming back is pure enjoyment.

“I enjoy coming back to the place where I went to high school and being around the students,” He said. “It keeps the marriage going. I’ve been married 63 plus years. My wife likes her space, and this way it works well. And I can use the extra fun.”